The internet is brimming with articles about the history of pearls, stories of famous pearls, and types of natural pearls. These are undeniably fascinating, but they are seldom relevant in day-to-day life. My aim is to pique your interest in cultured pearls, which are significantly more accessible in every sense and make frequent appearances in our daily lives.

Most people can tell you that pearls come from the sea. However, only a small percentage - even among those interested in buying pearls or even jewelers - can explain how pearls form, the types of pearls available pn the market, and the differences between them. In fact, relatively few people are aware that pearls can have shapes other than round or colors beyond white and cream.

Knowledge about the origin and types of pearls is more than just an assortment of interesting facts. It equips you to be an educated buyer who can't be easily misled. If you understand exactly what you're purchasing and the factors affecting its cost, you can navigate the pearl market more efficiently and ensure you're getting the best value for your money.

Let's start by clarifying some terms that often appear and cause confusion: natural, cultured, and artificial.

The last term, artificial, is pretty straightforward and explanatory. It refers to any synthetic material designed to mimic pearls, from cheap plastic beads to the beautiful and pricey Majorica pearls.

The first two terms, however, are frequently misunderstood.

In an industry that's been around for over a century, virtually 99.99% of the pearls on the market are cultured, meaning they're farmed under controlled conditions with human intervention.

Natural, wild pearls are pearls found randomly in the wild. Why randomly? Because systematic harvesting of pearl oysters is banned worldwide and has been for quite some time (since 1958), with a few exceptions (e.g., in Bahrain, where you'd need a local license and a local guide-diver to pearl dive, and they strictly monitor the number of oysters harvested).

To find just one commercially viable (beautiful!) natural pearl, you'd need to open anywhere from ten to a hundred thousand oysters (depending on the species), which, as you'd agree, amounts to genocide. Hence, these discoveries are, as I reiterate, accidental and very rare. Consequently, the price of a very ordinary natural pearl is high, and the price of a beautiful natural pearl is astronomical.

Both of the latter types (natural and cultured) are classified as real pearls, as defined by the industry.

Natural pearls have their own admirers and collectors. This is a separate realm, one that looks down on us mere mortals purchasing cultured pearls. It operates on a different scale, with prices, as I mentioned earlier, vastly higher, and it caters to a different circle of connoisseurs. There are dozens, if not hundreds, of natural pearl varieties, in contrast to the limited kinds of cultured pearls that can be counted on two hands, with fingers to spare.

Let's consider a couple of fundamental points that are essential for further understanding what a pearl is.

So, what is a pearl?

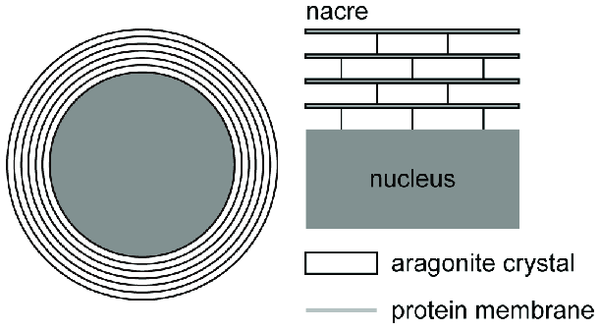

A pearl is a solid substance that grows either in the soft mantle tissue or the gonads of a living shelled mollusk. Like its host shell, a pearl consists of nacre called aragonite (aka calcium carbonate) deposited in concentric layers, and bonded by an organic substance called conchiolin (protein).

Under a microscope, the concentric layers of nacre appear as thin textured lines, similar to fingerprints. Although this texture is invisible to the naked eye, it produces a slight sand-like sensation when rubbed against the edge of your front teeth or another pearl. This, by the way, is the simplest way to distinguish a real pearl from an artificial one.

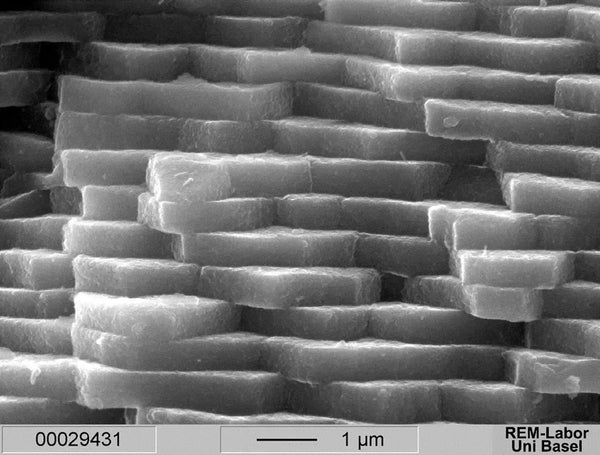

On a picture above: Microscopically thin layers of aragonite crystals, laid in plate-like arrangements, make up the foundational structure of pearls and oyster shells. Diffraction within these layers results in the highly prized iridescent effect known as "pearl orient" (inner glow) or Aurora effect. Photo: H. A. Hänni & Uni Basel.

To be continued...